Remember in mid February when that 6.3 magnitude earthquake hit Christchurch, NZ? This was before all the volcanoes started erupting, before all the tornadoes hit the US, before the tsunami and resulting nuclear crisis in Japan.....it seems like the year ought to be older. This is merely an interesting story about 2 bicycles who survived the quake.

About 3 years ago, I collaborated with Seven Cycles to build steel road bikes for a very nice couple from Grand Junction, who had retired and planned to spend a lot of time traveling and riding their bikes. Because of the travel we built them with S&S couplers, which, if you're not familiar, allow the bike frames to be broken down into two pieces and packed into an airline approved hardcase -- your bike is well protected and you don't get charged bike fees on the plane, which can run $100 per leg.

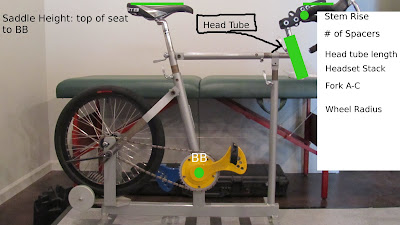

As with all the custom bikes I build, not only was the frame geometry full customized for their riding style and purpose, but the fork was rake-matched for optimal handling as well (eat your heart out twitchy stock bikes).

They rode these bikes all over and if the bikes had passports, the stamps in them would rival any globetrotter's. Paris, London, Sydney, all over the US..........you get the idea. I think in two years the bikes had been ridden about 12,000 miles and had flown upwards of 45,000 miles.

Spring of 2010, they came back and again told me how much they loved their bikes, but....

But, they wanted to be able to run bigger tires to handle some moderate off-road, muddy, gritty trails as well as be a little more forgiving on the rough cobbles common throughout Paris.

This time they opted for titanium bikes with S&S coupler (and custom paint to boot) that could fit up to 35mm tires. No compromises on function, of course, so we went outside to Waterford to build custom steel forks with the proper rake (in this case 58 mm) that fit the fatter tires and still had an appropriate axle to crown measurement to keep the head tube at the angle it was designed for.

The bikes were finished, and almost immediately whisked off to Paris to see the 2010 Tour. These bikes, like their steel siblings, traveled far and wide until late January 2011.

They were taken to New Zealand to tackle the Otago Trail. Two weeks of every trail and road condition imaginable and they had safely and successfully completed their mission. The bikes were cleaned as best as possible, and carefully packed away into their travel cases. They soon found their way to the concierge's locked storage at the Crowne Plaza Hotel in downtown Christchurch, while the owners continued site-seeing on foot the remainder of the trip.

On that late day in February the earthquake hit. My clients were in the lobby of the hotel, saying it felt like being in an elevator that suddenly drops, except that instead of dropping down, everything lurched sideways.

Like nearly everyone in that part of New Zealand, they fled to a safe area -- in this case a nearby park -- and took up residency with tarps and sheets of plywood supplied by the Kiwi government.

Everything was left at the hotel. Everything. Bikes, computers, cameras, clothes, GPS's, passports. With the help of the US Embassy and local government, they were able to finally make their way back to Colorado.

The Crowne Plaza Hotel, luckily is one of the most well built structures in Christchurch, and it didn't sustain major damage in the quake. However, buildings immediately surrounding it sustained serious structural damage and, like many buildings in the area had either collapsed or were threatening to, so nobody was even allowed in the area in the weeks following.

Without much information, aside from checking Google Earth images to check which buildings were still standing, they had no idea when or if they could expect to get their things back, but being the compassionate, pragmatic people that they are they always reinforced that they felt very lucky that the only thing they may have lost were things, while many others their lost much more.

Finally......

Nearly three months later, I received an email that they thought the bikes were on the way -- something had been sent from the hotel -- and they might be somewhere between Hong Kong and Cincinnati (?!??).

Well, they did show up:

It was clear that someone had opened up the hardcases on their way back into the US, and let's just say that they were not closed and re-packed with the utmost of care.

Both bikes were brought into the Studio, and aside from having to true all four wheels, replace some cables and housing and generally clean them up, they were in surprisingly good shape.

Besides a few scrapes and chips in the paint, the frames were perfect, but that wasn't too surprising: titanium frames, properly built can last about 200 years or so (steel is about 50 years, aluminum about 15 or so, and carbon is around 10 years).

So, things turned out okay, and the bikes live to travel on. I'm glad these rolling works of art and their owners, are able to roll around the world together for many years to come.